The Evolution of Romanitas in Inscriptions of the Post-Roman World

By Krish Sharma, Brookfield Academy (Brookfield, WI) 2024

Introduction

One of the most extensive repositories of Latin inscriptions, the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), faced a dilemma when it was created: do Roman inscriptions end at 476 AD, the traditional date marking the fall of the Roman empire? For historians, classicists, and students of Roman history around the world, 476 AD represents the end of the Roman empire and Roman dominance in Europe. However, the commission of the CIL agreed that it would be utterly wrong to end Roman inscriptions there because “most of the world of the sixth century (Constantinople under Justinian, Ostrogothic Italy) was still Roman from a social and cultural point of view” [1]. This view reinforces the idea that the boundary between the end of the Roman empire and the beginning of the Middle Ages is a gray area: where does Romanitas begin, and where did it end? To answer this question, we must discuss the importance of the time period known to historians as Late Antiquity. Late Antiquity is defined as the transition from classical antiquity into the Middle ages. Europe transitioned from a central Roman power to a group of divided nations. Late Antiquity was a period of change from the Roman ways but, in reality, was it really that different from the Roman period?

Throughout the existence of the Roman Empire in Western Europe, the Romans had a distinguishable cultural and political identity. Scholars coined the term Romanitas, or “Romanness,” in order to describe Roman political and social trends [2]. During the period of Roman domination, Romanitas fluctuated with the introduction of new societal roles such as new political offices or positions in the military structure. Subsequently, the shift in Romanitas after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD is not as drastic. The Romans and their ideas did not disappear without a trace; Romanitas continued to exist and affect the societies of non-Roman people who settled the lands of the former Roman Empire. To examine the changing idea of Romanitas, I will analyze several inscriptions that give insight into the sociopolitical atmosphere of their respective times. Inscriptions on gravestones, public buildings, or on coins give us a piece of real language that the public viewed [3]. By examining inscriptions from many parts of the Empire and from different time periods, we can see the continuity of political and social roles and gain insight into the deep, rich history that formed a sense of Roman identity by examining language, titles, and legacy, and how these examples of identity evolved throughout Late Antiquity.

Methodology

To examine trends in different facets of Roman society during various time periods, I will gather evidence from many types of sources. First, I will take a look at several inscriptions from the CIL. I carefully handpicked these inscriptions because I believe they display important facets of Romanitas through the evolution of the Latin language, societal titles, and the depiction of legacy. Although many inscriptions are hard to decipher, inscriptions are one of the most interactive pieces of evidence. Any inscription —whether it is on a public building, coin, or grave—is meant to be read by a broad variety of audiences and has a clear, defined purpose. By examining the purpose of these inscriptions, we can extract crucial information about Romanitas. In addition to these inscriptions, I will compare and contrast information displayed on the inscriptions with primary sources. These sources include ancient literature written about the inscriptions or historians' commentary about the inscription’s topic. By examining these sources thoroughly, we can extract the historical significance and the presence of Romanitas from each respective inscription.

Throughout Classical Antiquity, there were many various types of inscriptions on objects ranging from sculptures all the way to mosaics. However, we will be looking at three different types of inscriptions: inscriptions on coins, public buildings, and graves. In order to fully understand these inscriptions, we must discuss why these three forms of inscriptions are particularly significant. Coins reveal the crucial facets of society that were valued and respected by all. Whenever a coin was created, it was common practice to use these well-known symbols, creating a legible iconography. Inscriptions on public buildings contained pieces of identifying information which can be examined for instances of Romanitas. Everyday people in Ancient Rome viewed these public inscriptions, and thus, we can learn how the elite or ruling class of Rome wanted to be seen. Finally, epitaphs highlight important language used during the time period through the use of titles and other examples of Romanitas.

In order to properly discuss these inscriptions, we must also address the time period under question. Throughout all the vicissitudes of the Roman period of domination, significant issues arose around the third century. The Roman Republic, which stood in control of most of the known world, had collapsed with the rise of Julius Caesar and was replaced by the Roman Empire. Slowly, by 117 AD, the Roman Empire reached its largest area, extending from the territories in the Middle East all the way to modern-day Britain. However, through bloody power exchanges, Rome reached a turning point which most historians mark as the “Crisis of the Third Century” [4]. Bloody power switches, civil war, constant enemy invasion, and other pervasive issues plagued the empire. The Vandals, the Goths, and other neighboring tribes started defeating the Romans in battle for the first time in centuries. Enemies captured emperors and even killed them in battle. For example, leaders from a province of Rome called Gaul created a new empire to rise against Rome called the Gallic Empire. However, as the fourth century AD approached, Rome started to see a positive shift, pioneered by the leadership of a man named Diocles.

An up-and-coming officer on the Danube River, Diocles, killed Aper, the soon-to-be emperor, and changed his name from Diocles to Diocletian. Diocletian, after defeating several opponents, created a system of government known as the Tetrarchy. In order to understand the sociopolitical atmosphere of the period under question, it is crucial to understand the reasons and inner workings of the Tetrarchy. Diocletian realized that due to threats of foreign enemies it would be nearly impossible to defend the entire empire. Therefore, the Tetrarchy split the empire into two halves, the East and the West. In each half, there would be an Augustus, who would essentially serve as the emperor for that half, and there would be a Caesar, who would be appointed successor of the emperor [5].

In addition, there were also major changes in religion. Traditionally, the Romans believed in the pagan gods like Jupiter, Juno, and others. By the fourth century CE, paganism slowly lost its popularity, and Christianity became the dominant religion in Rome. The emperor Constantine converting to Christianity on his deathbed, the emperor Jovian working hard to reinstate Christianity, and laws protecting Christians all signaled a shift in religion in Rome. However, there was some backlash to Christianity. Emperors like Decius, Theodosius, and Julian were known to persecute and kill Christians. Therefore, it is important to understand that Christianity was becoming more and more popular but still had its opponents during this time period [6].

Licinius’s Statue Base and Roman titles

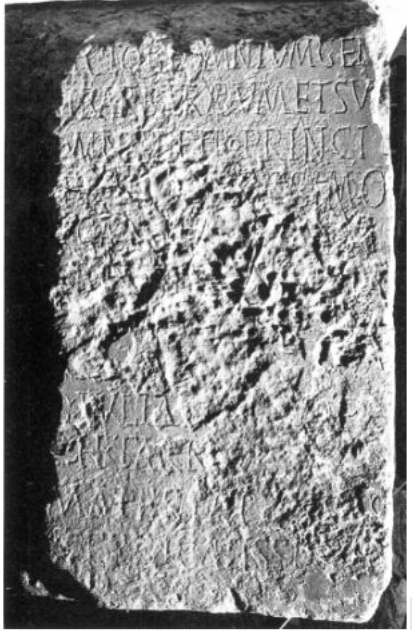

Fig. 1 Inscription on the base of a statue of V. Licinius Licianus, 4th c.

Prior to the fall of the Western Roman Empire, there are many inscriptions that give us an insight into existing Romanitas. Located in Tarraco, modern day Tarragona, a major city in the Roman province of Hispania, the following inscription (CIL II 4105/LSA-1980) occupies the base of a statue for Licinius, a Roman emperor during the early fourth century AD. By highlighting the importance of political offices in Rome and showing the glorification of Roman emperors, this inscription gives us insight into the Romanitas of fourth-century Rome.

Valerius Licinius Licinianus, similar to most emperors from the third and fourth centuries of Roman history, has an unknown upbringing; historian James Greary says that the Origo Constantini Imperatoris hints that he was born of peasant or common rank [7]. Similar to many Roman emperors, Licinius gained recognition through various military actions. First, working as an envoy for Galerius, Licinius was sent to negotiate with Maxentius, a usurper in Rome. Through these efforts, Licinius became a credible leader and Galerius granted him the position of praetorian prefect. By 308 AD, at a conference at Carnuntum, Licinius was elevated to the position of Augustus. In this inscription found on a base of Licinius’s statue, we see his glorification as an emperor even though, according to historian James Geary, he is infamous for being a mediocre emperor and persecuting Christians [8]. Although the statue may appear straightforward, it reveals many facets of Romanitas including religion, law, and politics.

CIL II-4105

Devictori omnium gen/tium barbararum et su/per omnes retro princi/pes providentissimo / imp(eratori), Caes(ari) [[[Val(erio) Lici]]]/[[[niano Licinio]]], p(io), f(elici), / invic(to) Aug(usto), p(ontifici) m(aximo), t(ribunicia) pot(estate), / (5) p(atri) p(atriae), co(n)s(uli) II, proc(onsuli). / Val(erius) Iulianus, v(ir) p(erfectissimus), / p(raeses) p(rovinciae) H(ispaniae) Tarrac(onensis), numi/ni maiestatiq(ue) eius / semper dicatissimus.

To the conqueror of all the barbarian people and the most provident above all emperors before, to the general, Caesar, Valerius Licinianus Licinius, pious, lucky, unconquered Augustus, pontifex maximus, with tribunicia potestas, to the pater patriae, twice consul, proconsul. Valerius Iulianus, vir perfectissimus, protector of the province Hispania Tarraconensis, always the most devoted to his divine spirit and majesty.

The inscription commences with “to the conqueror of all the barbarian peoples,” referring to Licinius’ rise as a commander against foreign people who lived in various provinces of the Empire. The word “barbarian” (barbararum) emphasizes the dominance of the Roman Empire over the rest of the Mediterranean world and underscores the way that Rome has historically belittled these tribes. The word referred to people who wore pants, opposed to the typical togas that the Romans wore, making the word an insult that implied superiority. Since their rise, the Romans have constantly destroyed enemy forces with the strength of their army, further instilling a sense of superiority above all others. It continues by calling Licinius the wisest emperor above all former emperors. These two lines of the inscription highlight a key feature of Romanitas: the past. The Romans used the past to define their leaders; they viewed their current leaders as greater than all of the ones before them. It proceeds with several important titles, starting with pio, felicio, invicto Augusto, meaning “pious, lucky, unconquered Augustus,” and heaping praise on the emperor Licinius. It then assigns the traditional terms of pontifici maximo, tribunicia potestate, and pater patriae to Licinius. These distinctly Roman titles highlighted the social hierarchy as created by Roman elites. In Rome, politicians were the most wealthy and most powerful individuals and comprised the majority of the upper class, and the titles they chose highlighted the importance of these institutions of religion and the state. The first of these titles, the pontifex maximus (head priest), represents the leader of one of the four ancient priestly colleges of Rome, the pontifices. This title was a political position held by famous Romans, such as Julius Caesar, during the Republic and became an honorary title bestowed upon emperors like Licinius [9]. The second title, tribunicia potestas (tribunal power), refers to the power of a tribune, a political office created around 500 BC that played a crucial role in Roman rights and politics [10]. The last of these titles, pater patriae, which translates to “father of the country,” was given to Romulus, the legendary first king of Rome, and subsequently given to Roman heroes like Camillus, Cicero, and Caesar, making it a term deeply rooted in Roman history, and one which was associated with many emperors as an honorific title [11]. These archaic titles correlate with the Roman view of Licinius as better than all previous emperors.

After a strenuous list of the emperor's various titles and powers, the inscription shifts its focus to the governor of the province in which it was located. Valerius Iulianus is described as holding the title of praeses or governor of Hispania Tarraconensis. The last line translates as “always most devoted to his divine spirit and majesty,” which references the importance of the governor and the idea of divinity in Roman culture. After the first king of Rome, Romulus, died, the Romans deified him as the god Quirinus [12]. Many emperors received a similar deification, as is demonstrated by Licinius’s glorification in this inscription. This phrase also points out that Valerius Iulianus is devoted to the emperor, making people’s devotion to the empire another important political concept. At the time, in order to gain more power and influence, it was crucial to be on the good side of the emperor. If the emperor favors you, you could be appointed to higher and more powerful offices. Valerius Iulianus’s almost godlike description of Licinius demonstrates the numerous examples of Romanitas found in this inscription. However, statue bases were not the only inscriptions that displayed Romanitas.

Valentinian I and Roman Currency

Born in modern day Vinoki in Croatia, Valentinian I was the son of Gratianus Funarius, a famous general under Constantine. Therefore, from a young age, he was destined to become involved with military affairs. Around 350 AD, there was an extreme struggle for power in Rome. The renowned father of Christianity in Rome, Constantine the Great, had passed away a few decades ago, and the empire was still split between his sons. However, Constantine’s sons were not able to preserve their power and were attacked by foreign usurpers. Therefore, Rome’s top generals scrambled for the position of emperor. For example, after the death of the emperor Julian, Constantine’s nephew, the military announced Jovian as the new emperor. However, Jovian was not able to defend Rome against Persian or any foreign attacks. Therefore, the military gathered at Nicaea to choose the new emperor. They offered the position to two men who declined until eventually they settled upon the qualified Valentinian [13]. This siliqua of Valentinian I displays the Romanitas of this era through the use of important symbols and figures.

Fig. 2 Siliqua of Valentinian I, 4th c.

A silver siliqua of Valentinian I was found in Trier or ancient Augusta Treverorum in the 4th century. The siliqua was a Roman coin, valued at 1/24th of the solidus by Isidore of Seville [14]. The back of the coin contains an important image of the goddess Roma, holding a spear in one hand and the Roman goddess of Victory, Victoria, in the other. The spear signifies the warlike Roman spirit, especially invigorated in the crisis of the third century when the empire was split up and there were always at least two different rulers at a time. In a prominent example of Roman virtues, famous Roman historian and author, Livy, states that the Romans claim to be descendants of the war god Mars in the story of their founding [15]. This anecdote explains why a Roman coin would depict a goddess holding a spear. The globe of victory in the left hand signifies the Roman spirit of success. The inscription on the front of the coin reads D N Valentinianus. The D N stands for Dominus Noster (Our Lord), another important title that was frequently used throughout Late Antiquity. In this context, it refers to how Roman emperors saw themselves as masters of the people, and the elite glorified the emperor. On the back of the coin, the all-important phrase “urbs Roma” conveys the significance of Rome even within its vast empire. This coin, thin and similar to a penny, would have circulated through the hands of many people. These ordinary people would have seen these symbols of Roman power, ingraining the image and reputation of the Romans as a strong empire into their minds. Although Rome during the period of Late Antiquity had lost control over the empire, and other cities like Ravenna or Constantinople rose to prominence, this coin nonetheless shows that even foreigners or “barbarians” used the idea of Rome as a source of legitimacy even though it was not necessarily the physical head of the empire anymore.

By examining coins, we get a view into the changing aspects and symbols of currency and can use them to draw conclusions about the changing nature of Romanitas. In contrast to the siliqua of Valentinian I, we have another siliqua of Valentinian III from a century later (Fig. 2). This time, instead of being issued on the authority of Valentinian III himself, this coin was issued by a foreign tribe, the Visigoths. The Visigoths and the Ostrogoths were the main two tribes of the Goths. Until 507 CE, when the Franks under the king Clovis took control and united all of Gaul, the Visigoths maintained leadership over the province. Under their first leader and chieftain Alaric, they sacked Rome in 410 AD [16]. When this coin was printed at some point between 439-455 AD, the Visigoths were still in control of Gaul. Even after this switch in power, we can see striking similarities and important differences by comparing the first and the second coin.

Valentinian III and Shifting Romanitas in Currency

Fig. 3 Siliqua of Valentinian III, 5th c.

In the fifth century AD, after the emperor Honorius died at Ravenna, a young five-year- old nephew of his was destined to take the throne. This young boy was Valentinian III. His early reign was mainly overseen by regents, particularly his mother Galla Placidia. This role of a female political figure marked a period of significant change in Roman history. While women in the imperial family had wielded influence for centuries, never before did a woman act as a regent to a future emperor, and in the years after, Galla Placidia’s daughter and other women of the Theodosian dynasty also held similar power. In addition, Valentinian III’s reign faced outside hostility from foreign invaders. For example, a nomadic tribe from eastern Europe called the Huns had a particularly dangerous leader who threatened the safety of Rome. This also demonstrates how, during this period of history, Rome faced imminent danger from stronger, outside tribes and they lacked the defensive resources and military might to fight back [17]. Similar to the example of Valentinian I, we can use the siliqua to examine these trends in Romanitas during the reign of Valentinian III.

When we compare the coins of Valentinian I and Valentinian III, the front sides are nearly identical, including the title of Dominus Noster, which is here given to Valentinian III, just as it was to Valentinian I. This shows that the Romanitas of this title continues even after this switch in power. Therefore, the coin, by displaying a Roman emperor on its front side, implies the continuity of the power of the Roman Empire in the area. Not only do we see that the image of the Roman Empire is the same, but also now the coin spreads the image of Roman power under non-Roman leadership. In this Visigothic empire, the Romanitas and the political implication of power that was tied to this coin rubbed off on all of the Visigothic people who used it in their day-to-day lives. Another key difference is that on the back of the coin where instead of the pagan god of victory, Victoria, we find the symbol of Christianity–showing the powerful change in religion from the fourth to fifth century. Roman emperors, like Constantine the Great, fervently spread Christianity throughout the Roman empire, and to see it on a Visigothic coin means that the influence of the Romans still existed and changed Visigothic culture. Religion and power are two main aspects highlighted by this Visigothic coin.

As seen in the two coins and statue base, varying symbolic features of Roman culture and society are evident on inscriptions during the beginning of Late Antiquity. Glorification of emperors, government titles, and the political structure of the government combined with the use of standard Roman symbolism on currency, Roman religion, and the benefits of identifying with the Romans are all aspects of the Romanitas of the times. These pieces of evidence give us a view into certain objects that a person living during Late Antiquity might see in their daily lives during the peak of Roman control. However, the question lies in what happened after the Romans lost control. Did Roman culture completely disappear? Did the Roman political atmosphere evaporate? By using the inscriptions from after the empire, we can see the continuity and discontinuity of this Romanitas through the use of titles, letters, and specific language.

Theodoric and the Continuity of Romanitas

A prominent example of the transition of Roman ideas after the fall of the Western Empire was the rule of Ostrogoths who adopted the Roman political offices, used Roman titles, and accepted and identified with the Romans as a part of their past. One of the most brilliant displays of Romanitas can be found in an inscription of the Roman politician Caecina Mavortius Basilius Decius (CIL 10.6850). Basilius Decius was a praefectus urbis Romae, and he was a high-ranking patrician, a vir illustris, known for draining the marsh of Decennorium. The Roman statesman Cassiodorus wrote about the Ostrogoths and recorded information about Basilius Decius. According to Thomas Hodgkin’s translation of Cassiodorus’s Letters, the praefectus urbis Romae was an office in control of city-related business like the corn, the sewers, and even the officers who took the census and were in charge of the public baths [18]. Basilius Decius was one of many prefects of Italy after the fall of the Roman Empire during a time when Italy was ruled by the Ostrogoths and, more specifically, Theodoric the Great.

In 476 CE, a man named Odoacacer, a ruler of the Goths, defeated Romulus Augustulus, marking the official end of the Roman empire. However, a certain man from the Amal tribe, by the name of Theodoric the Amal, rose to power and eventually overthrew Odoacer in 493 CE. Theodoric eventually held control over all of Italy. The reason why examining Theodoric is so vital is that he was a Gothic king, who, despite having a separate identity and culture than the Romans, worked to revive Roman culture and identity [19].

In addition, the following inscription discusses the marsh of Decennovium, a significant marsh along the path of the Via Appia. By discussing roles of politicians like Basilius Decius and glorifying the king Theodoric, this inscription displays various patterns of Romanitas.

CIL 10.6850

Dominus noster gloriosissimus adque inclytus rex Theodericus, victor ac triumfator, semper Augustus, bono rei republicae natus, custos libertatis et propagator Romani nominis, domitor gentium, Decennovii viae Appiae, id est a Tripontio usque Tarricinam, iter et loca, quae confluentibus ab utraque parte paludibus per omnes retro principes inundaverant, usui publico et securitate viantium admiranda propitio deo felicitate restituit: operi iniuncto naviter insudante adque clementissimi principis feliciter deserviente praeconiis ex prosapie Deciorum Caecina Mavortio Basilio Decio viro clarissimo et inlustri ex praefecto urbi, ex praefecto praetorio, ex consuleordinario, patricio, qui ad perpetuandam tanti domini gloriam per plurimos, qui ante non fuerant … albeos deducta in mare aqua ignotae atavis et nimis antiquae reddidit siccitati.

Our most glorious lord and the renowned king Theodoric, conqueror and victor, always Augustus, born for the good of the republic, guardian of liberty and propagator of the Roman name, conqueror of foreign people, he restored the path and region of the Via Appia, which is from Tripontium until Tarracina which flowing together from either part of the marsh had flooded through all emperors before, for public use and for the safety of travelers with the wonderful luck and with the luck of the god; diligently sweating for the ordered work and happily serving the most gentle emperor with praise, Caecina Mavortius Basilius Decius from the Decius family, the most distinguished man and illustrious from the prefect of the city, from the praetorian prefect, from the consul, patrician, who in order to perpetuate the glory of such great a lord through many people, who had not been before [lacuna] with the water led back into the sea, he returned the white [water] to a dryness unknown to the ancestors and exceedingly old.

The inscription commences with the words dominus noster gloriosissimus, signifying the concept of referring to the emperor as “the most glorious master” of the people. On the coins of Valentinian I and Valentinian III, we see the same word, dominus. This shows how Theodoric, a man who was not Roman, is being glorified in the exact same manner as Roman emperors were. It then proceeds to describe Theodoric as inclytus, meaning “renowned, “and the nouns victor ac triumfator, which signal his great military success. Then, Theodoric is said to be “born for the good of the Republic” (bono rei republicae natus). The idea of the Republic as well as the idea of serving the Republic itself is a political concept developed and cherished by the Romans during the Republic and beyond. Then, as Licinius was called the conqueror of all foreign people, Theodoric is called the domitor gentium, or “dominator of the foreign peoples.” It is important to note the difference in the language used in the description of these foreign people. The use of the word gentium in the first inscription contains the descriptive adjective barbarum, which means “barbaric. “However, in this inscription, there is no such negative terminology, and therefore we can see a shift in the view of foreign tribes, like the Visigoths, because they are in control in most of the former Western Roman Empire. While the Ostrogoths were ruling Italy, we see a clear similarity in the way that Licinius and Theodoric were described as rulers of their respective states. These titles frame Theodoric as a Roman ruler rather than a foreign or barbaric ruler.

Through the letters of Theodoric’s personal advisor, Cassiodorus, numerous references to his Roman titles and many Roman behaviors can be identified. For example, in one of Cassiodorus letters, Theodoric tells Cassiodorus to send an exquisite water clock that was used by the Romans to the Burgundian king, Gundibad, who was nearly going to wage war against the Ostrogoths. Theodoric uses this water clock as a symbol of power and intimidation, similar to how the Romans intimidated their enemies. Generally, in warfare, the Romans intimidated their enemies whether it was with the superior technology of their army or through their powerful social relationships [20]. As a vast empire, Rome created a sense of dominance that is echoed by Theodoric in Cassiodorus’s letters.

Going back to Basilius Decius’s inscription, we see the phrase “propagator Romani nominis” attributed to Theodoric. Translated as “propagator of the Roman name,” this phrase summarizes the importance of Theodoric. As a ruler in Italy after the fall of the Roman empire in 476 CE, Theodoric creates a sense of continuity between the supposed fall of the Western Roman Empire, and he makes us question whether the fall of the Roman Empire was truly the ultimate end of Romanitas. After this quick praise to the ruler, it switches to the main topic of discussion, the draining of the marshes of the Decenovium of the Via Appia, which runs from Tripontio to Tarracina (Tripontio usque Tarricinam). It states that the marsh has been flooded from all sides “per omnes retro principes,” meaning “through all past emperors.” Here, we see the repeated use of the words “retro principes” and the emphasis on being new and better. Even though this inscription is composed and inscribed by entirely different people, we still see the same language being used to refer to new inventions and innovations. It then proceeds to talk about how the marsh is restored and open to the public, transitioning to highlight the man who headed the project, Caecina Mavortius Basilius Decius, a member of the famed Decian gens. A group of political titles is given to Basilius Decius praefecto urbi, praefecto praetorio, and patricio. The second title, the praetorian prefect [21], is a renowned position created by Augustus that overlooked the praetorian guard. This continuity shows that, even under an Ostrogothic king, Roman titles first instituted as early as Augustus are still preserved and being used. Then, the inscription displays the idea of qui ante non fuerat, meaning “what was not here before,” referencing the opening of the flooded marshes for travelers. Basilius Decius and Theodoric accepted their Roman past and invoked Romanitas in the draining of the Decennovium, signifying their embrace of Roman political and social motives. The clear presence of Romanitas in this Ostrogothic inscription symbolizes the strong continuity of Roman ideas after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Liberius’s Epitaph and Romanitas in Legacy

Another informative type of inscriptions can be found in the form of grave inscriptions, or epitaphs. The purpose of an epitaph is to commemorate the glory and legacy of a person. By reading the following epitaph of a well-known patrician and politician, Liberius, one can see numerous instances of Romanitas.

Petrus Marcellinus Felix Liberius was one of the most interesting characters of the period of Late Antiquity. Not much is known about him, except for an epitaph that is left behind in the CIL. As a man who lived through the aftermath of the Roman collapse, he was a praetorian prefect in Italy, Gaul, and Egypt [22], and this epitaph is no less interesting than Liberius himself [23]. Written in elegiac couplets, his epitaph contains references to old phrases and his titles as an accomplished politician after the fall of Rome (CIL 11.382):

Humano generi legem natura creatrix

Hanc dedit, ut tumuli membra sepulta tegant.

Liberii suboles patri matrique sepulchrum,

Triste ministerium, mente dedere pia.

Hic sunt membra quidem, sed famam non tenet urna,

Nam durat titulis nescia vita mori.

Rexit Romuleos fasces currentibus annis

Successu parili Gallica iura tenens,

Hos non imbelli pretio mercatus honores,

Sed pretio maius detulit alma fides.

Ausoniae populis gentiles rite cohortes

Disposuit, sanxit foedera, iura dedit.

Cunctis mente pater, toto venerabilis aevo

Terdenis lustris proximus occubuit.

O quantum bene gesta valent. cum membra recedunt,

Nescit fama mori, lucida vita manet.

Nature, the creator of human kind,

Gave this law, that burial mounds should cover buried limbs.

The children buried with a pious mind

For their father and their mother, a sad duty to discharge.

Here are certain limbs. but the urn does not hold his fame.

For his life lasts by titles that cannot die

He wielded the fasces of Romulus as the years ran by

Holding the Gallic laws with equal success

He did not buy these honors at an unwarlike price

But at a greater price his nourishing loyalty conveyed.

He duly put down the family cohorts for the people of Ausonia,

He enshrined treaties, gave laws.

With all in the mind the venerable father recently lay dead

with his whole age in 30 periods of 5/4 years.

Oh how well deeds prevail, as the limbs give way,

Fame does not know to die, bright life remains.

This inscription opens with the idea of “Humano generi legem natura creatrix,” implying that the burial rite of a man was a process given to humankind by law. It continues with “tumuli” and “sepulchrum,” extending the idea of the traditional Roman process of burying the dead. Here again, we see the use of the antiquarian Roman tradition of using a tumulus, or mound of dirt, to cover the bodies of the dead [24]. The inscription then transitions to speaking about Liberius's funeral urn itself. “Famam non tenet urna,” meaning “the urn does not hold the fame,” signifies that his dead, buried body did not appropriately represent his fame or legacy, and also suggests that the urn was not sufficient to contain his legacy in death. Another interesting part of the epitaph is the line “Nam durat titulis nescia vita mori,” which implies that Liberius’ titulis, or titles, are immortal and last beyond death [25]. One of these titles, his consulship, is referred to by the term “Romuleos fasces,” alluding to the legendary first king of Rome and the bundle of sticks that symbolized the power of a dictator in early Rome [26]. The epitaph highlights his title of praetorian prefect in Gaul when it says “Gallica iura tenens,” referring to the Gallic laws that Liberius made as praetorian prefect. This epitaph was from the sixth century almost 1000 years after the common use of these Roman terms, showing the extended significance of the Roman political titles and offices in Late Antiquity. In the final lines, “pater” hints that the epitaph was written by his children and glorifies Liberius as “Nescit fama mori, lucida vita manet,” which translates as “Fame does not know how to die, bright life remains” and signifies the everlasting effects of Liberius’s accomplishments. Another important feature of the epitaph is its form. The poem consists of elegiac couplets, a meter already familiar from the work of earlier Roman poets like Ovid, Catullus, and Propertius. It is important to recognize the reuse of older Roman vocabulary and cultural terms as well as the connection to a significant meter of the Augustan age in the epitaph of Liberius. By examining this relatively obscure inscription from after the fall of the Roman empire, we see the use of typical Roman language and a common Roman meter, showing the existing Romanitas of the time period.

Conclusion

By examining coins, epitaphs, and bases of statues, we can extract an enormous amount of information about the story of Romanitas. Coins serve historians as a real piece of how the Roman government and leadership wanted to be seen by the public. Inscriptions on public buildings or roads also signify social and political values of Roman leaders and elites. Epitaphs can also give us real evidence of how people wanted to be viewed and the role of legacy during Late Antiquity. From the prominence of Romanitas during the height of Rome’s power through the downfall of the Roman Empire, these inscriptions show the continuity of Roman political and cultural ideas, even as they were deployed by people who were not traditionally identified as Roman. During Late Antiquity, the Romans lost power in Western Europe, and many barbarian tribes like the Ostrogoths and Visigoths seized power, bringing in their own cultures and traditions. But to what extent were their cultures Roman? The ancient ritual of covering the body with a tumulus, the glorification of their rulers, or the use of ancient titles show the continuity of Roman culture after 476 AD, reaffirm the CIL’s decision that Western Roman history did not end when the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed.

However, one may ask the complex question: when did Romanitas wear off on the world? The simple answer is that Romanitas never ended. Roman culture thrives in our daily lives, although unknown to most people. In most major cities in the United States, you can find a Latin inscription. For example, one of the most famous monuments in the United States, the Washington Monument, contains a Latin inscription on the top of its aluminum cap that says “Laus Deo,” meaning “Praise to God.” By examining the lives of ancient figures on epitaphs, the evolution of titles throughout time periods, and even the changes in language over time, we can glean information about changes and transformations in ancient society. These transformations can display positive and negative effects of certain actions in the past. These are some of the many examples of Romanitas in the modern day that display why examining past historical trends can be so crucial to shape a better future.

Notes

1 Tantillo, “The Epigraphic Cultures of Late Antiquity,” 59.

2 Adams, “Romanitas and the Latin Language”, 184.

3 Khan and Vaidya, “Inscriptions : As A Source of History,” 195.

4 Cary and Scullard, “A History of Rome,” 507.

5 Ibid., 517-518.

6 Heichelheim and Yeo, “A History of the Roman People,” 423.

7 Gearey, “Persecution of Licinius,” 4-5.

8 Ibid., 1-2.

9 Oxford Classical Dictionary, 1219-1220.

10 Ibid., 1549-1550.

11 Ibid., 1121.

12 Cary and Scullard, “A History of Rome,” 39.

13 Heichelheim and Yeo, “A History of the Roman People,” 435.

14 Isidore of Seville, Etymologiarum libri XX, Liber XVI, 25.

15 Livy, “Ab Urbe Condita,” Book 1.

16 Jordanes, “The Origin and Deeds of the Goths.”

17 Heichelheim and Yeo, “A History of the Roman People,” 477.

18 Hodgkin, “The Letters of Cassiodorus,” 87-88.

19 Heichelheim and Yeo, “A History of the Roman People,” 480-481.

20 Martin, “The Roman Empire: Domination and Integration,” 721-723.

21 OCD, 1241.

22 Ibid.

23 O’Donnell, “Liberius the Patrician,” 32-33.

24 OCD, 755.

25 Ibid., 544.

26 Ibid., 587-588.

27 National Park Service, “Washington Monument.”